(The Sentinel) – Kansas legislation that created the Special Education Task Force directs it to “study and make recommendations for changes in the existing formula for funding of special education and related services.” Instead, the task force voted to recommend an increase of $82.7 million in special education funding over four years without discussing inconsistencies in the formula.

After about an hour of testimony, Chairperson Melanie Haas asked task force members to make and vote on recommendations. Haas didn’t even allow task force members to ask questions of those presenting testimony, which is customary.

The majority, who all work in different aspects of the education system, even rejected a motion to study and discuss inconsistencies that show funding was adequate and more money was not necessary.

The vote to recommend more funding was 6-4, with all Republican legislators on the panel opposing the measure. Rep. Valdenia Winn (D-Wyandotte), who is also a local school board member, and all the other school representatives voted for the increase without any study.

The witness list for the hearing featured several organizations known for advocating higher K-12 spending in the state, such as the Kansas Association of School Boards, the Kansas National Education Association, Game On for Kansas Schools, and the Kansas Parent Teachers Association. Education professionals and parents of SPED students also urged the panel to add its support to that of the Kansas State Board of Education. The State Board unanimously endorsed the four-year funding hike at its meeting last July.

Special Education Task Force ignored obvious flaws in the funding formula

Opponents of the rush to judgment contended that special education would be fully funded but for flaws in the formula. They also noted a flaw that results in many districts receiving more than 92% reimbursement of their costs. Committee member Rep. Kristey Williams spoke about the flaws in the funding formula:

“We have a situation where there is money attributable to special education students, but we are not counting any of it. We are not counting the Local Option Budget for one. But what about additional weightings that are attributable to special education students that also aren’t counted; At-Risk, ELL (English Language Learner) and transportation; all those are negated out of the formula. But other things are strangely counted; a virtual number of 12,000 students that throw off the excess costs as well. There is layer after layer after layer of errors in the formula, and that only happens when the formula is updated over a series of years but not done holistically or comprehensively.

“So, we can throw more money on it and ignore the fact that the federal government is $300 million short every year; we can ignore the fact that the legislature adds between 30 and $50 million annually of additional money above and beyond the Gannon decision, and we can ignore the fact that every single special education student has money attributable to the fact that they’re enrolled in that district and we count almost none of it. We count their base ($5,500), but eliminate five weightings.”

Dave Trabert, CEO of Kansas Policy Institute, which owns The Sentinel, offered that school districts accusing the Legislature of violating the law by not fully funding SPED services are ignoring state statutes themselves:

“A 2019 state audit determined that districts were not spending at-risk funding as required by state law, and another audit in 2023 found at-risk funding is still not being spent as required by state law.

“Some superintendents refuse to allow school board members to participate in – let alone conduct – the needs assessment meetings. Many school boards are just given staff-prepared summary reports to approve.

“Many school districts refuse to comply with state laws designed to improve student achievement but loudly cry foul if they believe they are being denied funding. The fact that their financial records indicate that many districts do not need more special education funding further compounds the irony.”

Trabert’s testimony cited data from the Department of Education that shows school districts increased their special education cash reserves by $63 million over the last 15 years, and other operating cash reserves more than doubled. School districts began the 2024 school year with $1.25 billion in carryover cash reserves, most of which represent state and local taxpayer funding from prior years that wasn’t spent. Trabert said the only plausible explanation for the increases is that school officials provided all the services they believed to be necessary and had money left over to increase cash reserves, as they surely would have dipped into cash reserves if they believed more money needed to be spent.

He also testified about the formula flaws referenced by Rep. Williams.

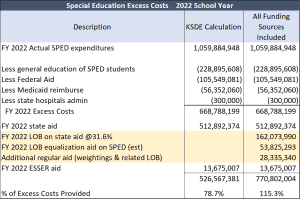

The formula that determines funding to be provided gives the state credit for some weightings (money provided above the base), but not for all weightings. It also gives credit for some of the Local Option Budget funding related to special education, but not all of it. KSDE officials previously told legislators that they don’t know why all the funding isn’t counted.

The amounts excluded are highlighted in yellow in the adjacent table. Had they been in the formula, the state would have reimbursed districts for 115% of their excess costs.

Trabert said mistakes happen when legislation is written, and it’s likely that the exclusions are just mistakes. He said the Special Education Task Force should either identify rational legislative intent to exclude some of the funding related to special education or recommend that the formulas be adjusted.

The Special Education Task Force recommendations will be forwarded to the Legislature, which failed to pass a similar measure in 2023.