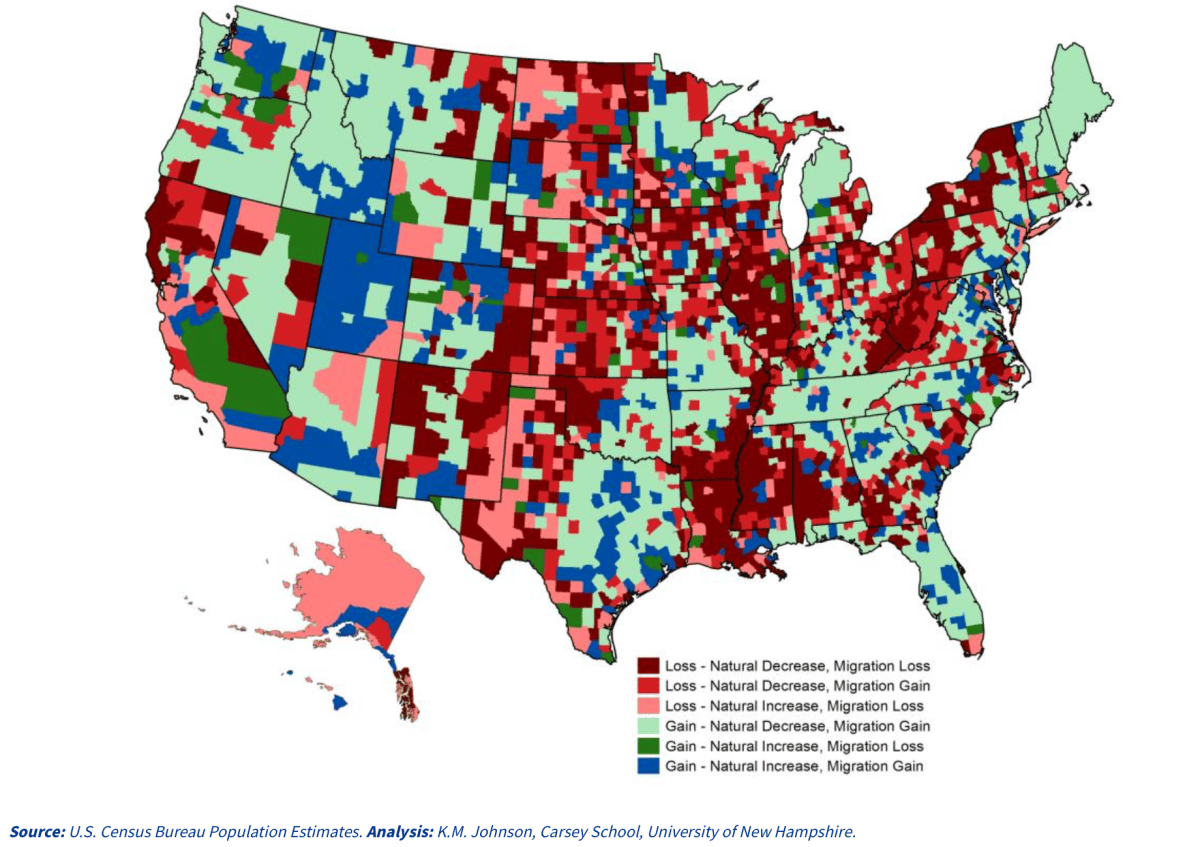

(The Sentinel) — Seventy-eight Kansas counties lost population between 2020 and 2022, with the remaining 27 posting gains, according to demographic data from the U.S. Census Bureau.

The Sunflower State’s post-COVID recovery in population backslid in 2022, after a microscopic increase of only three from 2020-21. As of last year, Kansas’ population stood at 2,937,150.

Of the 10 largest counties in the state, gainers and losers of population were split evenly: Butler, Douglas, Johnson, Leavenworth and Sedgwick showed increases, while Riley, Reno, Saline, Shawnee and Wyandotte experienced what demographers refer to as negative domestic migration, or more U.S. residents leaving a location than moving in, is a primary cause of the decline.

Of the 10 largest cities in Kansas, again an even split: Lawrence, Lenexa, Olathe, Overland Park (a net gain of four) and Shawnee increased in population from 2020-22, while Kansas City, Manhattan, Salina, Topeka and Wichita lost residents.

Other items of interest from Census data:

- 14 of the 32 largest cities lost population

- While Johnson County gained, the cities of Leawood, Prairie Village, and Roeland Park saw reductions

- Not all Western Kansas saw declines; Comanche, Gove, Graham, and Gray all saw increases during the period

Kansas is alone in the region with its declining population. The closest state also losing population is Illinois.

The reasons for more people moving out of Kansas than moving in? Kiplinger’s uses state income tax rates, average combined state and local sales tax levies, and median property tax rates to judge “Tax-Friendly States for Middle-Class Families” and “Tax-Friendly States for Retirees”, and finds Kansas wanting in both cases. Kansas is the sixth-worst for middle-class families and the third-worst for retirees.

Additionally, 2023 research from Rich States, Poor States shows Kansas has the third-most government employees per 10,000 population in the United States, trailing only Alaska and Wyoming. An over-regulated economy is another drag on employment opportunities, causing job creators and job seekers to go elsewhere.

Policy implications for states with stagnant or declining populations are discussed in an article from the Pew Charitable Trusts:

“Population trends are tied to states’ economic fortunes and government finances. More people usually means more workers and consumers adding to economic activity as they take jobs and buy goods and services, which generates more tax revenue. A growing economy, in turn, can attract even more workers and their families. The reverse is usually true for states with shrinking or slow-growing populaces.

“State officials study population trends, in addition to other measures, to forecast revenue streams and residents’ demands for services for budgeting purposes and long-term fiscal planning. The size of a state’s population, and annual changes, also factor into how much it will receive from some federal grants.”