(The Sentinel) — Microschools, which provide opportunities for enterprising teachers and parents to find alternatives to the public school system, are gaining traction across the country — and indeed, even here in Kansas.

First coming to local attention in 2020 during the pandemic, microschools are small, usually independent schools that typically serve no more than 10-15 students. They are a relatively new concept that has emerged as an alternative to traditional public schools and homeschooling. Microschools are designed to provide personalized and individualized learning experiences for students, with a focus on project-based learning and student-led exploration.

They are generally run by educators or parents looking for a more customizable learning experience for their children, and may be located in homes, community centers, or rented spaces, and may be organized around a specific theme or subject area. Some microschools may also utilize online learning platforms and resources to supplement in-person instruction.

Devan Dellenbach runs a rural microschool. Courtesy Kerry McDonald

Devan Dellenbach runs a rural microschool. Courtesy Kerry McDonald

One such school in Kansas is in the tiny town of Abbyville, just a little over 20 miles from Hutchinson in Reno County. The Re*Wild Family Academy is situated in this town of just 83 souls.

According to Forbes’ education contributor Kerry McDonald, it was founded earlier this year by former public school teacher Devan Dellenbach. The rural microschool currently serves about 10 homeschoolers of varying ages, and is expanding this fall to include more children and more offerings.

Dellenbach and her husband — also an educator — run the school out of their home.

Dellenbach, according to Forbes, left public education to homeschool their first child — now 14 — rather than put her on a bus for 45 minutes each way to get to the nearest public school.

According to Forbes, Dellenbach — under financial pressure — was considering returning to teaching, but a friend talked her into starting her own school.

“Dellenbach currently charges $25 a day per student, which includes drop-off instructional time, enrichment and curriculum support from 9:00 am to 3:00 pm. It also includes a nutritious, homemade lunch that Dellenbach prepares,” McDonald wrote. “Her program is currently offered one day a week but will be growing to three days a week this fall. Dellenbach tried to price her program based on what local families could afford, and she offers flexible options, but $25 a day is still financially out of reach for many families.”

That sort of financial burden would be alleviated if the Legislature approves education savings account legislation in SB 83, which would provide means-tested funds that parents can use to send students to something other than a public school.

“A number of Republicans and Democrats privately said they understood that many students will not get a good education without choice, but they wouldn’t vote for it because they are more concerned about their re-election prospects,” writes Dave Trabert, CEO of Sentinel parent company Kansas Policy Institute. “It’s easy to find an excuse to vote ‘no’ because of a minor provision in the bill, but it’s just that – an excuse. These legislators know that by opposing SB 83, they are condemning tens of thousands of students to a lifetime of underachievement.”

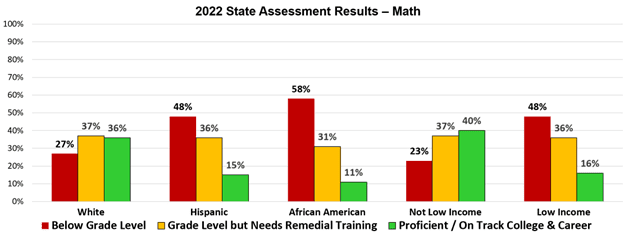

Nearly half of low-income students in Kansas are below grade level in math, and only 16% are proficient. By comparison, a quarter of students who are not low-income are below grade level, and 40% are proficient.

SB 83 would provide close to $5,000 per student that could be used to pay tuition.

Microschools are a boon for students and educators

McDonald likewise reports that — contrary to popular belief — microschools can help neurodiverse students as well.

“A common criticism regarding microschools, learning pods, unschooling approaches and other non-traditional educational models is that they don’t work well for, or exclude, neurodiverse learners, including those on the autism spectrum or those who have dyslexia, ADHD or other special learning needs,” McDonald wrote.

The reality is much different.

Forbes found another microschool in Wichita, Kansas, that is part of the national Prenda microschool network.

Wildflower Community School was founded in 2021 by Wichitans Molly and Noah Stephenson, who have two children with dyslexia who were not being well served by their public schools.

According to Forbes, the Stephensons found success with unschooling, or “self-directed education that is centered around a child’s individual interests and goals,” and connected with other local homeschoolers who were doing the same.

“Over the subsequent years, as they realized that all of their five children are neurodiverse, this non-coercive learning approach became a crucial way to support their children’s education.”

They currently have 35 students in their school — only four of whom would be considered “neurotypical.”

“Most have specialized learning needs, several are on the autism spectrum and more than 20 would be characterized as having ADHD,” McDonald writes. “They had to turn away many more students due to capacity constraints.”

The entrepreneurial nature of microschools has been good for many of the educators involved as well, some of whom have ended up making as much — or more — that they did when teaching in the public school system, and with more freedom to teach students in ways that maximize learning.

A robust ESA program — such as Florida has — in Kansas would allow many more students to have the same opportunity.