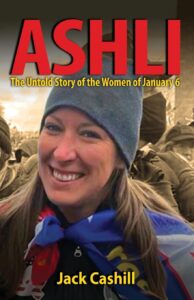

(Editor’s note: The following is an excerpt from Jack Cashill’s new book, ASHLI: The Untold Story of the Women of January 6. It is named for Ashli Babbitt, who was shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer although she was unarmed.)

In the Netherlands, they call it “Dolle Dinsdag” or, in English, “Crazy Tuesday.” That was the day in 1944 that the Dutch took to the streets in celebration believing that the Allies had liberated their country from Hitler’s grasp.

In the Jacobin Thunderdome, Crazy Tuesday came on a Friday, Octobert 7, 2016. That was the day the Washington Post dropped the infamous Access Hollywood tapes. In newsrooms and boardrooms and teachers’ lounges across America, the enemies of Donald Trump celebrated, convinced that they had been liberated from their own imagined Hitler.

“When you’re a star, they let you do it. You can do anything. … Grab ’em by the pussy. You can do anything,” Trump was heard telling television host Billy Bush on this 11-year-old tape.

Democrats popped corks and RINOs stampeded for the exits.

“I am sickened by what I heard today. Women are to be championed and revered, not objectified,” said Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan – who promptly withdrew from a campaign appearance with Trump the following day in his home state of Wisconsin.

That same Saturday, RNC Chairman Reince Priebus hit Trump with a sobering assessment. “I’m hearing,” said Priebus, “that you can either withdraw or you can lose in the biggest landslide that’s ever been had.”

Trump stood firm, and the rest is history. He understood his female supporters better than the RINOs did, better than the pollsters did, and much better than the media did. Writ large, they were a far hardier crew than their female counterparts on the left or in the GOP’s squishy middle.

That Trump had been divorced twice, married three times, and filed for bankruptcy six times did not alienate his base. If anything, it made him more relatable. What they saw in Trump was a man whose life had been as messy as the subject of a Hank Williams song, but who, praise the Lord, had seen the light or at least something like it.

Modern journalists didn’t know Hank Williams from Serena Williams. Cosseted from birth and college-bred, they knew little of the struggles that define life in Flyover Country, the kind of struggles that find their outlet in country and western music – poverty, loneliness, joblessness, heartbreak, addiction, D-I-V-O-R-C-E.

Unlike many activists on the left, however, the women of the right respect the idea of marriage, of family, of faith, of country. They have no interest in revolution. If anything, they want restoration. They live their lives believing in a Judeo-Christian world order even if they don’t always live up to its expectations.

The killing of Ashli Babbitt

On first learning of Ashli Babbitt’s death, the media attacked her much as they had Trump.

Aware that the fatal shooting of an unarmed female veteran would undermine the saga already in play – of law enforcement’s heroic battle to “save democracy” – journalists promptly shared the imperfections of her life.

Their collective goal was to deny Ashli martyr status – by any means necessary. The New York Times set the tone. Within a day of the shooting, a trio of Times reporters had dug up just about every seemingly wayward blip in Ashli’s adventurous life.

Yes, she had been divorced, married twice, fallen into debt, and once gotten into an altercation with a former girlfriend of her second husband, Aaron Babbitt. These enterprising reporters had managed to retrieve the complaint filed by the girlfriend and quote it extensively – all of this within 24 hours of Ashli’s being shot and killed.

What the reporters overlooked was the ability of women like Ashli to overcome adversity.

There was a good deal to overcome. Born to an unmarried mother in 1985, Ashli caught a break as a toddler when Roger “Rocky” Witthoeft came into her mom’s life. Rocky and Micki would have four children together, all of them boys. The rough-and-tumble Ashli adapted well. Micki refers to her as the “quintessential big sister.”

As the only girl in a family of five children, Ashli grew up as something of a tomboy in Lakeside, California, a “rodeo town” of about twenty-thousand people twenty or so miles inland from San Diego.

Coming of age at a time when the state was still the stuff of dreams and songs, Ashli lived the archetypal life of a young Californian – swimming, riding horses, playing water polo and soccer, doing gymnastics.

San Diego has a long history as a military town, and Ashli fell under that influence. She was particularly close to her maternal grandfather, Anthony Mazziott, a Navy vet who helped raise her when she was a little girl. Sixteen when Islamic terrorists attacked the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Ashli redoubled her commitment to join the military.

Once she turned eighteen, she did just that and would spend the next fourteen years in the Air Force, either on active duty, as a reservist, or in the Air National Guard.

Ashli ‘activated, not radicalized’

While on active duty, Ashli met the man who would become her first husband, Tim McEntee. “She was a baby when they married,” said Micki. “They helped each other through some really hard times.” Their separate deployments put a strain on the marriage, but they maintained “love and friendship,” added Micki, even after the marriage dissolved.

In 2015, a defense department publication caught up with Senior Airman Ashli McEntee as she was about to leave on her eighth deployment, this time to “an undisclosed location in Southwest Asia.” She had previously been deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. As a veteran of overseas missions, Ashli served as something of a mentor to young airmen on their first deployment.

“The newer airmen have been coming to us and asking about the living conditions, the weather, the gear, the schedule, how we work as teams, the hours we work,” Ashli told the interviewer. “As we have a large amount of first timers deploying with us, I think we can offer comfort and knowledge.”

While still in the National Guard, Ashli started working at the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Plant in Maryland on a security detail. It was there she met Aaron Babbitt, a bearded man as brawny and gruff as Ashli was cute and petite. Micki was thrilled when the couple returned to San Diego County and purchased a pool supply company. “I have been blessed to have two good sons-in-law,” said Micki. Ashli and Aaron married in June 2019.

“Ashli was not radicalized,” said Micki. “She was activated.”

Micki and her family had several years to watch Ashli transform from passive citizen to outspoken protestor. “My sister was 35 and served 14 years – to me that’s the majority of your conscious adult life,” Ashli’s younger brother Roger Witthoeft told the Times. “If you feel like you gave the majority of your life to your country and you’re not being listened to, that is a hard pill to swallow. That’s why she was upset.”

Jack Cashill’s new book, ASHLI: The Untold Story of the Women of January 6, is available in all formats.